Notes

This section is intended for trivial amusements and ephemeral thoughts in their unorganized form — think of social media posts without interactions. Please allow for errors and imprudence. Also archived here is a selection of my older posts from Twitter and Weibo, neither of which I remain active on. Posts may be removed without notice if they are developed into formal articles or no longer reflect my current opinions.

Subscribe to these notes (excluded from the main feed).

February 2026

Note (2026-02-15 10:15)

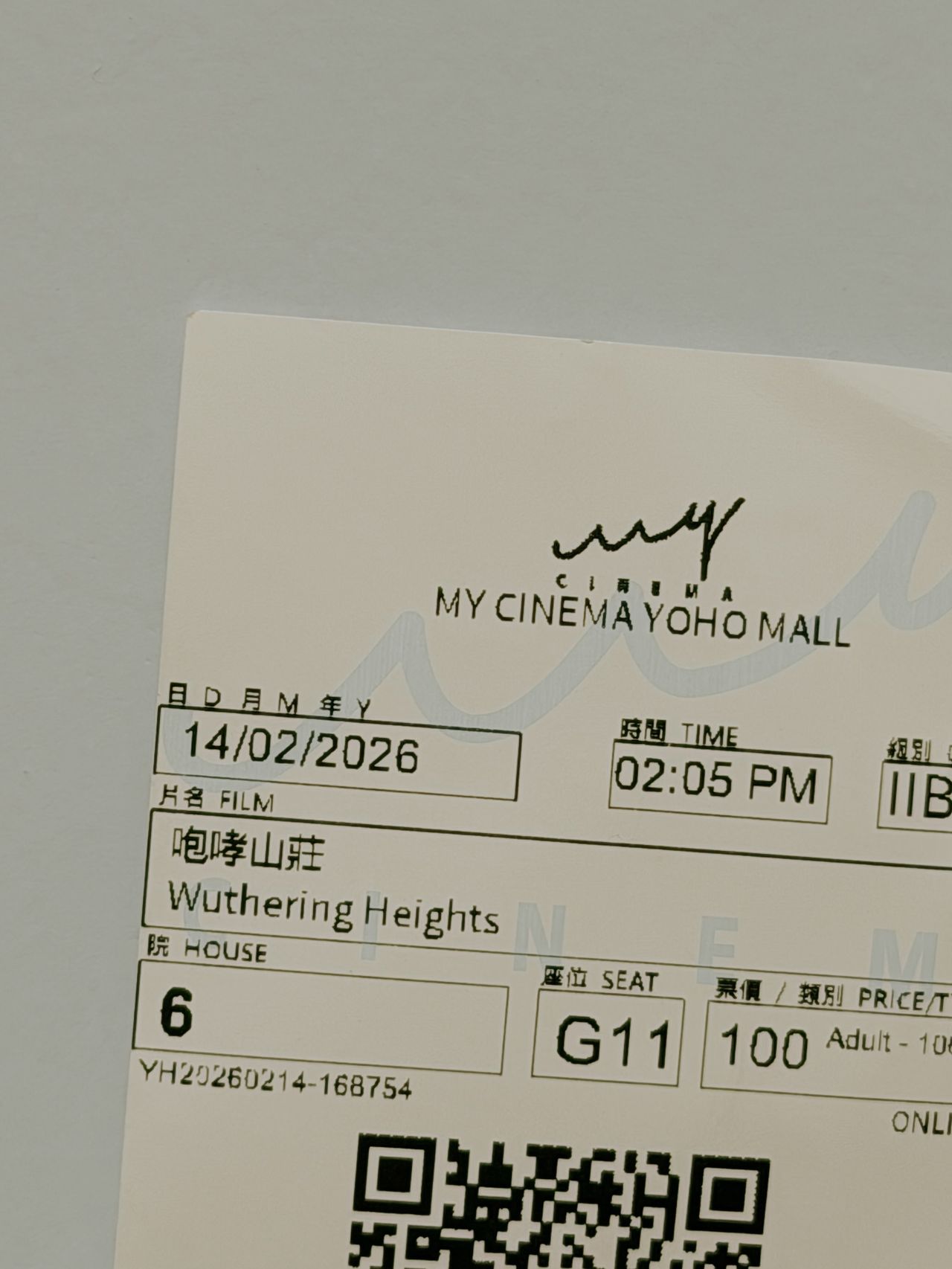

Note (2026-02-14 22:05)

sometimes you just find yourself having bought a ticket to a weird show despite obvious red flags and decide to squeeze your eyes shut and make the best of it.

Note (2026-02-11 14:37)

what did i do to deserve this

Hong Kong and British Culture, 1945–97 (2026-02-07 15:14)

Hampton, Mark. Hong Kong and British Culture, 1945–97. Hong Kong University Press, 2024.

香港的回歸,反而為英國提供了一個展示國家成就的機會:包括在香港建立法治、市場經濟以及高效率和無貪腐的政府——這些成就甚至被延伸為整個英國帝國成就的象徵。

The Handover, rather, provided an occasion to reflect upon British accomplishment in establishing markets; rule of law; and effective, corruption-free government: properties that could be extended rhetorically to the entire British Empire.

英國在香港直到 1980 年代初才真正受到挑戰的持續管治,卻為所謂英國的德治提供了一個正面的展示。

Britain’s continuing management of Hong Kong, decisively challenged only in the early 1980s, offered a site in which supposed British virtues could be more positively showcased.

戰後早期曾有這樣的論點:儘管中國可以隨時收回香港,但卻似乎不太會在短期內有此舉動。而這觀點在 1980 年代與 1990 年代也得到迴響:就是雖然中國最終也會收回香港,但出於利益的考慮,中國是不會對香港進行激烈變革的。

[T]he early postwar argument that, although China could reclaim Hong Kong any time it wanted, it was unlikely actually to do so in the near future, was echoed by assertions in the 1980s and 1990s that, although China was, after all, going to reclaim the colony, self-interest would ensure that the Communists did not impose radical change on it.

當時在香港的華人多是抱着過客的心態,他們「反正從未真正地把這個地方當成自己的家,甚至到現在也還未有這個想法,儘管最後會有」,對他們來說,香港有機會回歸中國這件事並不需要特別去關心。

[A]t least for the Chinese in Hong Kong, most of whom were sojourners who had ‘never really regarded the place as their home anyhow and have not quite begun to do so even now, though they will’, the possibility of Hong Kong’s return to China was not particularly arresting.

港英政府雖是對倫敦負責,但實際上卻有越來越多的自主權,並往往會為着地方的利益而犧牲大英本土的利益。

Although responsible to London, in practice the Colonial Government enjoyed increasing autonomy and often pursued local interests even to the detriment of metropolitan British interests.

而不尋常的是,與戰後初期的全球趨勢不同,當時香港政府官方上奉行自由放任的經濟政策,這與第三世界採取的發展主義模式以及西歐的凱恩斯主義混合經濟,形成了鮮明對比。但在實行中香港其實並非是完全的自由市場經濟體系,而是旨在「以最低成本促進貿易和經濟增長」的經濟體系,當需要維護香港及華人精英的利益時,政府會果斷地干預經濟。

Unusually for the early postwar era, Hong Kong officially identified with laissez-faire, standing in sharp contrast with the developmentalist model adopted in the Third World and the Keynesian mixed economies of Western Europe. In reality, Hong Kong was less of a free market economy than one designed to ‘promote trade and economic growth at the lowest possible costs’, and the Government did not hesitate to intervene in the economy when the interests of colonial and Chinese elites required it.

[…] More

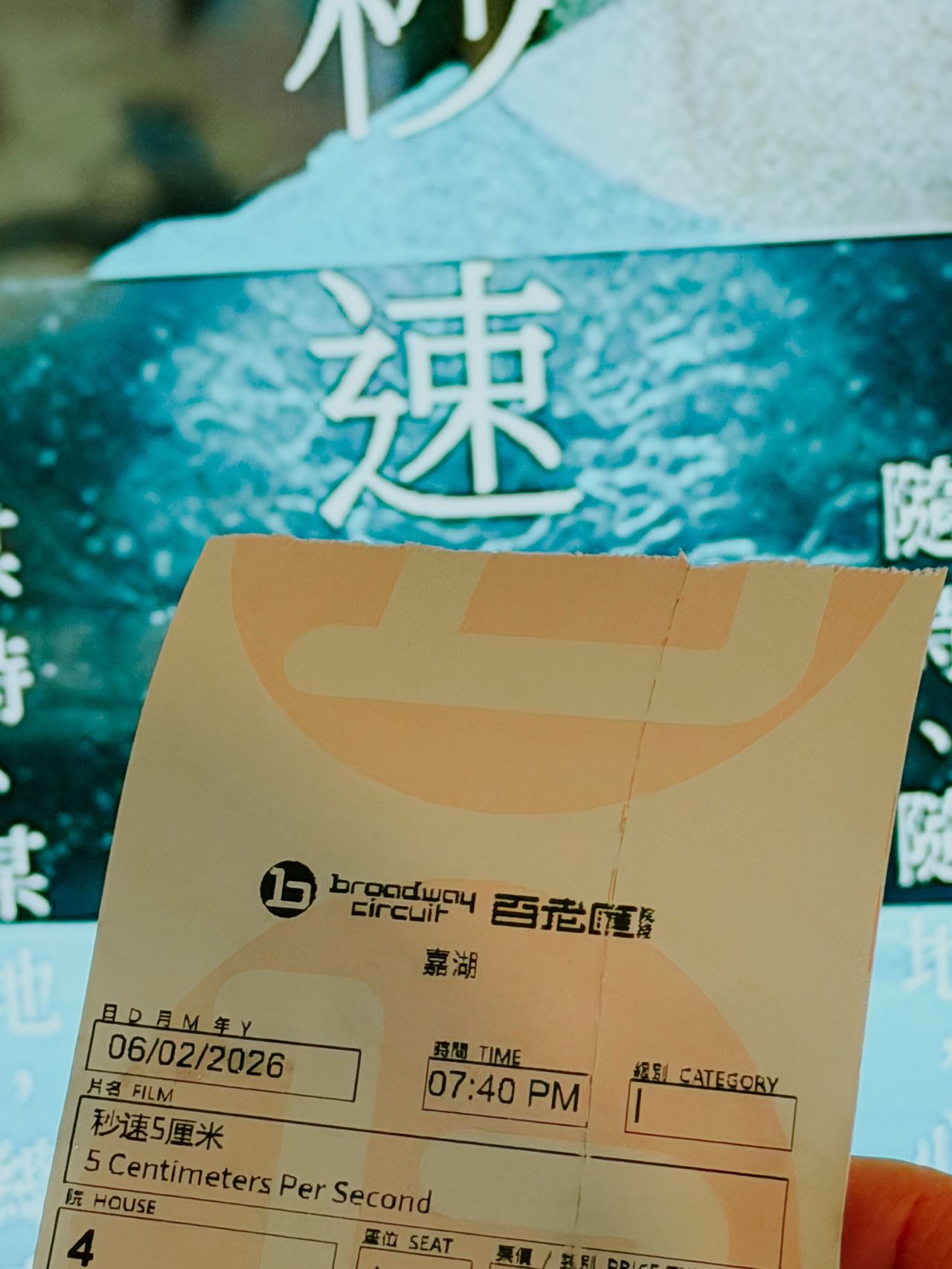

5 Centimeters per Second (2026-02-07 14:28)

Despite my unhealthy rewatch count for 5 Centimeters per Second, I find it a difficult recommendation, primarily due to the utter lack of conventional drama. There is no confrontation, no villain, no reckoning, just a linear collage of mundane events driven by unavoidable departures and unspoken feelings that are arguably lamentable, but in no way tragic. One is left to decide whether this restraint is the point — the capacity of the everyday to wound — or a limitation of the storytelling itself.

There is a serendipitous symmetry in having first watched the anime at the protagonists’ age at the story’s beginning, and now rewatching this adaptation at their age at the end. I couldn’t help but wonder what I had felt watching the original anime in my early teens, and why I was so impressed that I felt almost compelled to go see this adaptation. Remember I could not. Maybe it’s just rose-colored nostalgia. Or maybe, as the protagonist herself suggests, that’s the formative residue of an early age at work.

The adaptation expands and rearranges the original material with mixed results. Some additions feel thin, and the newly introduced coincidences strain credibility more than they enrich the narrative. The story may simply be too spare to bear expansion. Yet the reconstructed scenes still evoke the memory of watching and rewatching the same file on a portable player, a video that once took hours to download and felt worth every minute of waiting.

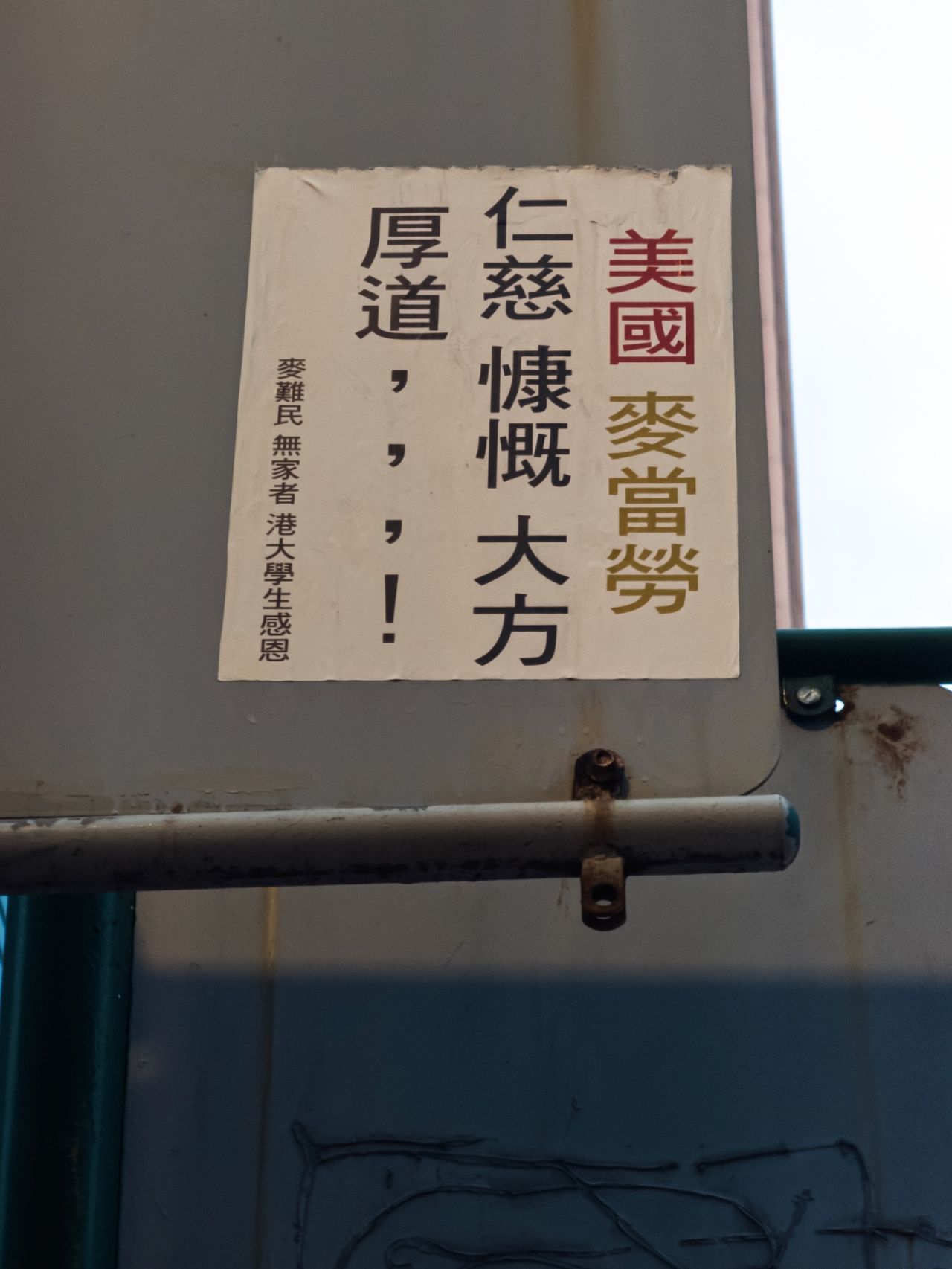

Note (2026-02-07 10:20)

I don’t even want to expel [anger]. I love anger. I’m so grateful for anger. I think it’s led me to make every strong, good decision in my life that I’ve made.

I’m too fucking mad. I’m going to figure out how to do it right and how to do it better. I’m going to heal the parts that need healing so that I don’t recreate these patterns. And it’s hard work, but anger is so mobilizing that it can get you through, I think, any amount of work. Like, thank God for anger. I think sadness can really keep me stuck in the trenches. And anxiety can keep me kind of debilitated and unable to make a decision. But, my God, anger will get me off the chair, making some decisions, moving forward and doing the work.

Note (2026-02-06 22:22)

Note (2026-02-06 22:20)

“Intimacy as a Lens on Work and Migration”:

Intimacy as a lens means starting from people’s emotions, sense of self, and relationships with other people, and using these micro-scale negotiations as a starting point to advance social inquiry.

One hesitation I had about using ‘intersectionality’ is that the boundaries between different social positionings are not always stable and unchanging. Some scholars call this ‘intra-categorisation’ to problematise the categories and the boundaries that are used to inscribe them (McCall 2005). These unsettled boundaries are particularly salient in my project, as I discuss how being an ethnic minority is not a given fact, but something people must constantly practise and negotiate with.

One example is the ambivalence many informants feel when they talk about whether they are ‘authentic’ ethnic minorities. That means they are officially registered as coming from a minority background, yet they feel ambivalent about this identity—and sometimes do not even feel a strong sense of belonging linked to it. This sometimes also leads them to feel guilty. They feel they should know more about their ethnic culture, yet, as the younger generation who has grown up under the twin influences of the state’s ‘Han assimilation’ approach and globalisation, they are gradually losing touch with this aspect of their identity.

Even though emotions are often theorised in relation to people’s private lives (such as their family lives and intimate relationships), I find it helpful to understand emotions in social spheres that are often assumed to be unemotional. In this book, I wrote about migrants’ emotional encounters with the migration regime (that is, the hukou system), and how these encounters are highly emotional and therefore require them to exercise their ‘emotional reflexivity’ (Holmes 2010; Burkitt 2012)—that is, the ability to draw on one’s own and other people’s emotions to navigate a complicated situation that lacks a specific ‘feeling rule’ (Hochschild 1979). Migrants’ emotions when encountering an opaque migration regime also have much to tell in terms of revealing the mechanisms of mobility inequalities and an overall ‘emotional regime’ existing at the broader societal level. In the field of psychology, emotions are often regarded as ‘signals’ and can inform us about a person’s mental state. This ‘signal’ function of emotions can also be useful in sociology, as emotions are often revealing of the structural inequalities in which people find themselves, and they are valuable in revealing the ways power works in producing and maintaining inequality.

[…] More

Note (2026-02-06 17:22)

“The Japanese Ethics of ‘Ningen’ Dethrones the Western Self”:

The basic methodology of modern, Western philosophy is the same, according to Watsuji: a philosopher from a specific cultural and historical background reflects upon how they conceive of the structure of their mind, and declares that what we might call their ‘self-referential abstraction’ is the universal model that theoretically applies to every sentient being across all space and time.

What makes the modern conception of the subject that commits this ‘self-referential abstraction’ so problematic, according Watsuji, is that it had to come up with a supra-individual self that aims at the happiness of society or the welfare of mankind, in order to cloak the foundational problem of individualistic self-centredness. What is worse, Watsuji argues, is that, despite this move towards intersubjective consciousness, the conception of the modern subject creates conflict between human subject as the source of ethical values, and the objective world or nature as meaningless ‘thereness’. Nature, in this case, is conceived of as a heteronomous other – a threat to human autonomy, an irrational outside entity that needs to be conquered through the self-determining intelligibility of ‘I think.’

The Japanese conception of human being (ningen sonzai, 人間存在) in the larger context of East Asian philosophies is radically different from the Western conception of humanity. What makes us human (ningen) is not the ontological structure made by the first principle or divine transcendence. Nor is it reason, spirit, nor even the metaethical structure of meaning that provides a theoretical ground for our ethical values, but rather the ‘concrete practice of betweenness’ or ‘in-betweenness of act connections’ that constitute our humanity (ningen-sei, 人間性). And this practice of betweenness always already comes with the practical self-awareness of emptiness.

[…] More

Note (2026-02-02 16:07)

“The New Yorker offered him a deal”:

All my life, I’ve heard about this thing, “the New Yorker story”. I hadn’t investigated this term in depth, but I understood it to mean “a short story that is meandering, plotless, and slight—full of middle-class people discussing their relentlessly banal problems”.

Not only were these stories similar to each other, but they also seemed quite different from other literary stories. These stories were mostly marked by their extreme restraint. They didn’t just eschew plot, they also eschewed lyricism, symbolism, surrealism, or any other devices that would call attention to themselves. Their plotlessness made them seem highbrow, but their unadorned style made them highly accessible.

If you’ve ever seen a New Yorker cartoon, you understand this early style of New Yorker humor. It’s not meant to be laugh-out-loud funny. Instead it’s mordant, dry, and slightly obscure. The journal assumes the reader will understand whatever is supposed to be funny.

The editors of the journal encouraged prospective writers to use this style.

This [] requirement [to decline ‘dizzy’ stories, i.e., those with a more florid, maximalist style, or lots of figurative language,] was in part necessitated by the editor, Harold Ross, who absolutely refused to print any story that he couldn’t understand. Ross also hated any discussion of sex or immorality. Even adultery could only be hinted at or alluded to. His magazine couldn’t contain anything that might give bad ideas to a child.

The New Yorker story was defined by three things: the first was Katherine’s determination to print something very different from what you’d see in other journals; the second was Ross’s mandate that all stories be perfectly clear and comprehensible and clean; and the third was the literary ambitions of The New Yorker’s stable of contributors.

[…] More

January 2026

Note (2026-01-26 15:06)

“How I Estimate Work as a Staff Software Engineer”:

[S]oftware engineering projects are not dominated by the known work, but by the unknown work, which always takes 90% of the time. However, only the known work can be accurately estimated. It’s therefore impossible to accurately estimate software projects in advance.

In other words, I don’t “break down the work to determine how long it will take”. My management chain already knows how long they want it to take. My job is to figure out the set of software approaches that match that estimate.

If you refuse to estimate, you’re forcing someone less technical to estimate for you.

Note (2026-01-25 18:10)

Note (2026-01-25 14:05)

Time has become diaphanous. I’ve failed to label my own personal eras. Without those labels, events bleed. And given more time, they bleed more.

Note (2026-01-22 23:31)

saw an article whose title i find particularly relatable — “i’m addicted to being useful.” so freaking i am.

Note (2026-01-19 20:55)

Note (2026-01-19 17:19)

Note (2026-01-18 12:41)

Note (2026-01-14 15:02)

Note (2026-01-13 22:17)

“How Consent Can—and Cannot—Help Us Have Better Sex”:

It’s widely accepted that a woman really can consent to sex with a husband on whom she is financially dependent. The immediate though rather less accepted corollary is that she can also consent to sex with a paying stranger. To say anything else, many feminists now argue, would be to infantilize her, to subordinate her—to the state, to moralism—rather than acknowledge her mastery of her own body.

Perhaps, some philosophers suggest, we should not be able to forfeit future consent, either by agreeing to serious bodily injury or death or by entering into a contract that strips us of long-term agency. But, if football players can consent to beat each other up on the field, why can’t we beat each other up in bed? If we want to forbid people from subjugating themselves in the pursuit of their fantasies, we’d have to criminalize both extreme forms of B.D.S.M. relationships and marriage vows that contain the word “serve.”

Critics of this shift worry about encounters where both parties are blackout drunk, or where one appears to retroactively withdraw consent. They argue that a lower bar for rape leads to the criminalization—or at least the litigation—of misunderstandings, and so discourages the sort of carefree sexual experimentation that some feminists very much hope to champion.

[T]he bureaucratization of our erotic lives is no path to liberation.

[A] cultural emphasis on consent—and especially “enthusiastic consent”—has divided “sex into the categories awesome and rape” (Fischel), ignored the complexity of female desire (Angel), and reinforced the notion of sex as something that women give to men, rather than something that equal people can enjoy together (Garcia).

Note (2026-01-13 22:00)

“Heidegger knew that we are always outside, weathering the storms”:

[W]e inhabit [the world] as that in and through which our lives take place and make sense. The world is not a container but the meaningful context in which we dwell. We are in the world in the way that someone is in love or in business.

It is in order to deny our facticity and its associated vulnerability that we want to think of ourselves as indoors. A sovereign, self-enclosed substance is not tied to the destiny of anything else. It does not depend on anything in order to be but exists all by itself. Thinking of ourselves in this way is a self-protective strategy. It purports to make us invulnerable: Deus Invictus, God invincible and unbound.

We are not and cannot be Deus Invictus but must be – if I may put it this way – Homo Implexus, the human being entwined and entangled. The truth is that we are vulnerable beings who live outdoors, amidst other things and at stake in them. To pretend otherwise is to deny the sober truth of your essential finitude as being-in-the-world.

So, if we try to pretend that we dwell indoors, we may win a faux feeling of invincibility. But we lose something more important: our openness to being moved. As Franz Kafka put it: ‘You can withhold yourself from the sufferings of the world; … but perhaps this very act of withholding is the only suffering you might be able to avoid.’

[…] More

Note (2026-01-04 21:03)

Note (2026-01-01 22:02)

“No, Hong Kong’s Governance Is Not Becoming Like China’s. It’s Actually Worse.”:

Despite the authoritarian system under Beijing’s rule, mainland authorities do possess institutional mechanisms that absorb public pressure and enforce administrative responsibility in ways Hong Kong currently does not.

While mainland China is also guilty of suppressing criticism and dissent, it has the structural tools to pursue at least modest accountability, and the confidence to allow a tightly controlled safety valve for the fiercest anger.

Many of [Hong Kong’s] key accountability mechanisms were designed and institutionalized during the final decades of British rule, when the colonial government sought to develop Hong Kong into a prosperous global city grounded in professionalism, public accountability, and the rule of law.

These mechanisms, however, can function effectively only in a political environment that favors checks and balances.

Hong Kong has hollowed out the institutional mechanisms that once ensured accountability and effective governance, but it has not developed the structures that support stability in mainland China. The result is a governance vacuum, in which neither democratic nor authoritarian accountability functions effectively.

This structure traps Hong Kong between two governance models. It has weakened the institutions that once supported its administrative legitimacy, yet it cannot adopt the systems of performance-based accountability that make Chinese authoritarianism sustainable. In this context, political suppression becomes one of the few viable tools available to manage discontent.

As long as Beijing values the appearance of “One Country, Two Systems,” Hong Kong will not be able to replicate the mainland’s approach to crisis governance. But without rebuilding its own institutions of transparency and responsibility, the city risks further erosion of public trust and administrative capacity.

December 2025

Note (2025-12-28 21:39)

Note (2025-12-27 10:42)

The problem was setup.py. You couldn’t know a package’s dependencies without running its setup script. But you couldn’t run its setup script without installing its build dependencies. PEP 518 in 2016 called this out explicitly: “You can’t execute a setup.py file without knowing its dependencies, but currently there is no standard way to know what those dependencies are in an automated fashion without executing the setup.py file.”

This chicken-and-egg problem forced pip to download packages, execute untrusted code, fail, install missing build tools, and try again.

PEP 658 [putting package metadata directly in the Simple Repository API] went live on PyPI in May 2023. uv launched in February 2024. uv could be fast because the ecosystem finally had the infrastructure to support it. A tool like uv couldn’t have shipped in 2020. The standards weren’t there yet.

Wheel files are zip archives, and zip archives put their file listing at the end. uv tries PEP 658 metadata first, falls back to HTTP range requests for the zip central directory, then full wheel download, then building from source. Each step is slower and riskier. The design makes the fast path cover 99% of cases.

Some of uv’s speed comes from Rust. But not as much as you’d think.

pip copies packages into each virtual environment. uv keeps one copy globally and uses hardlinks (or copy-on-write on filesystems that support it).

uv parses TOML and wheel metadata natively, only spawning Python when it hits a setup.py-only package that has no other option.

[…] More

Note (2025-12-25 20:09)

“Why Millennials Love Prenups”:

For much of the twentieth century, judges almost always refused to enforce prenups, fearing that they encouraged divorce and thus violated the public good. They were also concerned that measures to limit spousal support could lead to the financially dependent spouse—usually the woman—becoming reliant on welfare. Nonetheless, in the twenties, as divorce rates increased, potentially pricey payouts became a topic of national debate. As the sociologist Brian Donovan observes in the 2020 book “American Gold Digger: Marriage, Money, and the Law from the Ziegfeld Follies to Anna Nicole Smith,” a veritable “alimony panic” set in. To avoid paying any, men transferred deeds, created shell companies, and, in New York, set up “alimony colonies” in out-of-state locales such as Hoboken, where they wouldn’t be served with papers. Even though courts were equally loath to award alimony—“Judges publicly criticized alimony seekers as ‘parasites,’ ” Donovan writes—the perception that men were being fleeced persisted.

There had been limited cases since the eighteenth century in which prenuptial contracts were recognized in the U.S., but these typically pertained to the handling of a spouse’s assets after death. The idea of a contract made in anticipation of divorce was considered morally repugnant. In an oft-cited case from 1940, a Michigan judge refused to uphold a prenup, emphasizing that marriage was “not merely a private contract between the parties.” You could not personalize it any more than you could traffic laws.

But by the early seventies there was no stemming the tide of marital dissolution: the divorce rate had doubled from just a decade earlier. In 1970, a landmark case, Posner v. Posner, was decided in Florida. Victor Posner, a prominent Miami businessman, was divorcing his younger wife, a former salesgirl. He asked the judge to honor the couple’s prenup, which granted Mrs. Posner just six hundred dollars a month in alimony. The judge, in his decision, acknowledged the cultural shift: “The concept of the ‘sanctity’ of a marriage as being practically indissoluble, . . . held by our ancestors only a few generations ago, has been greatly eroded in the last several decades.”

[…] More